Climate Impacts on Ecosystems

On This Page:

On This Page:

- Overview

- Timing of Seasonal Life-Cycle Events

- Range Shifts

- Food Web Disruptions

- Threshold Effects

- Pathogens, Parasites, and Disease

- Extinction Risks

Overview

Climate is an important environmental influence on ecosystems. Changing climate affects ecosystems in a variety of ways. For instance, warming may force species to migrate to higher latitudes or higher elevations where temperatures are more conducive to their survival. Similarly, as sea level rises, saltwater intrusion into a freshwater system may force some key species to relocate or die, thus removing predators or prey that are critical in the existing food chain.

Climate change not only affects ecosystems and species directly, it also interacts with other human stressors such as development. Although some stressors cause only minor impacts when acting alone, their cumulative impact may lead to dramatic ecological changes.[1] For instance, climate change may exacerbate the stress that land development places on fragile coastal areas. Additionally, recently logged forested areas may become vulnerable to erosion if climate change leads to increases in heavy rain storms.

Changes in the Timing of Seasonal Life Cycle Events

For many species, the climate where they live or spend part of the year influences key stages of their annual life cycle, such as migration, blooming, and reproduction. As winters have become shorter and milder, the timing of these events has changed in some parts of the country:

- Earlier springs have led to earlier nesting for 28 migratory bird species on the East Coast of the United States.[1]

- Northeastern birds that winter in the southern United States are returning north in the spring 13 days earlier than they did in a century ago.[2]

- In a California study, 16 out of 23 butterfly species shifted their migration timing and arrived earlier.[2]

Because species differ in their ability to adjust, asynchronies can develop, increasing species and ecosystem vulnerability. These asynchronies can include mismatches in the timing of migration, breeding, pest avoidance, and food availability. Growth and survival are reduced when migrants arrive at a location before or after food sources are present.[2][3]

Range Shifts

As temperatures increase, the habitat ranges of many North American species are moving north and to higher elevations. In recent decades, in both land and aquatic environments, plants and animals have moved to higher elevations at a median rate of 36 feet (0.011 kilometers) per decade, and to higher latitudes at a median rate of 10.5 miles (16.9 kilometers) per decade. While this means a range expansion for some species, for others it means movement into less hospitable habitat, increased competition, or range reduction, with some species having nowhere to go because they are already at the top of a mountain or at the northern limit of land suitable for their habitat.[4][5] These factors lead to local extinctions of both plants and animals in some areas. As a result, the ranges of vegetative biomes are projected to change across 5-20% of the land in the United States by 2100.[4]

For example, boreal forests are invading tundra, reducing habitat for the many unique species that depend on the tundra ecosystem, such as caribou, arctic foxes, and snowy owls. Other observed changes in the United States include a shift in the temperate broadleaf/conifer forest boundary in the Green Mountains of Vermont; a shift in the shrubland/conifer forest boundary in New Mexico; and an upward elevation shift of the temperate mixed/conifer forest boundary in Southern California.

As rivers and streams warm, warmwater fish are expanding into areas previously inhabited by coldwater species.[5] As waters warm, coldwater fish, including many highly-valued trout and salmon species, are losing their habitat, with projections of 47% habitat loss by 2080.[4] In certain regions in the western United States, losses of western trout populations may exceed 60 percent, while in other regions, losses of bull trout may reach about 90 percent.[5] Range shifts disturb the current state of the ecosystem and can limit opportunities for fishing and hunting.

See the Agriculture and Food Supply Impacts page for information about how habitats of marine species have shifted northward as waters have warmed.

Food Web Disruptions

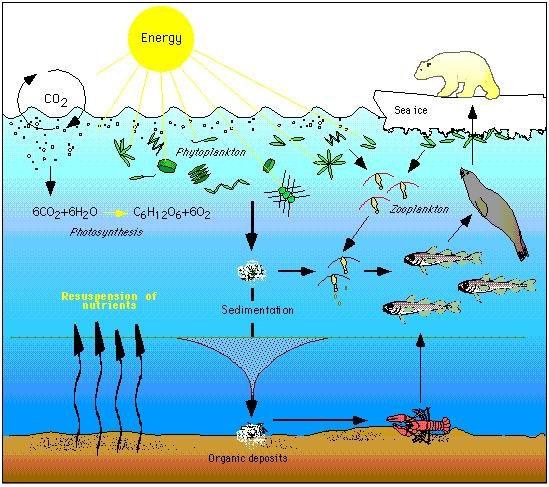

The impact of climate change on a particular species can ripple through a food web and affect a wide range of other organisms. For example, the figure below shows the complex nature of the food web for polar bears. Not only is the decline of sea ice impairing polar bear populations by reducing the extent of their primary habitat, it is also negatively impacting them via food web effects. Declines in the duration and extent of sea ice in the Arctic leads to declines in the abundance of ice algae, which thrive in nutrient-rich pockets in the ice. These algae are eaten by zooplankton, which are in turn eaten by Arctic cod, an important food source for many marine mammals, including seals. Seals are eaten by polar bears. Hence, declines in ice algae can contribute to declines in polar bear populations.[2][6][7]

The Arctic food web is complex. The loss of sea ice can ultimately affect the entire food web, from algae and plankton to fish to mammals. Source: NOAA (2011)

The Arctic food web is complex. The loss of sea ice can ultimately affect the entire food web, from algae and plankton to fish to mammals. Source: NOAA (2011)

Click the image to see a larger version.

The Pika

Climate change is likely the leading factor decreasing the populations and shifting habitat range of the American pika (Ochotona princeps). Source: National Climate Assessment (2009).

Climate change is likely the leading factor decreasing the populations and shifting habitat range of the American pika (Ochotona princeps). Source: National Climate Assessment (2009).Penguins and Climate Change: A Case of "Winners" and "Losers"

Even within a single ecosystem, there can be winners and losers from climate change. The Adélie and Chinstrap penguins in Antarctica provide a good example. The two species depend on different habitats for survival: Adélies inhabit the winter ice pack, whereas Chinstraps remain close to open water. During the past 50 years, a 7–9°F increase in midwinter temperatures on the western Antarctic Peninsula has led to a loss of sea ice. Over the past 25 years, the population of Adélie penguins decreased by 22%, while the population of Chinstrap penguin increased by an estimated 400%.[13]

Buffer and Threshold Effects

Ecosystems can serve as natural buffers from extreme events such as wildfires, flooding, and drought. Climate change and human modification may restrict ecosystems’ ability to temper the impacts of extreme conditions, and thus may increase vulnerability to damage. Examples include reefs and barrier islands that protect coastal ecosystems from storm surges, wetland ecosystems that absorb floodwaters, and cyclical wildfires that clear excess forest debris and reduce the risk of dangerously large fires.[4]

In some cases, ecosystem change occurs rapidly and irreversibly because a threshold, or "tipping point," is passed. One area of concern for thresholds is the Prairie Pothole Region in the north-central part of the United States. This ecosystem is a vast area of small, shallow lakes, known as "prairie potholes" or "playa lakes." These wetlands provide essential breeding habitat for most North American waterfowl species. The pothole region has experienced temporary droughts in the past. However, a permanently warmer, drier future may lead to a threshold change—a dramatic drop in the prairie potholes that host waterfowl populations, which subsequently provide highly valued hunting and wildlife viewing opportunities.[8]

Similarly, when coral reefs become stressed from increased ocean temperatures, they expel microorganisms that live within their tissues and are essential to their health. This is known as coral bleaching. As ocean temperatures warm and the acidity of the ocean increases, bleaching and coral die-offs are likely to become more frequent. Chronically stressed coral reefs are less likely to recover.[5][9]

Pathogens, Parasites, and Disease

Climate change and shifts in ecological conditions could support the spread of pathogens, parasites, and diseases, with potentially serious effects on human health, agriculture, and fisheries. For example, the oyster parasite, Perkinsus marinus, is capable of causing large oyster die-offs. This parasite has extended its range northward from Chesapeake Bay to Maine, a 310-mile expansion tied to above-average winter temperatures.[10] For more information about climate change impacts on agriculture, visit the Agriculture and Food Supply Impacts page. To learn more about climate change impacts on human health, visit the Health Impacts page.

Extinction Risks

Climate change, along with habitat destruction and pollution, is one of the important stressors that can contribute to species extinction. The IPCC estimates that 20-30% of the plant and animal species evaluated so far in climate change studies are at risk of extinction if temperatures reach the levels projected to occur by the end of this century.[1] Global rates of species extinctions are likely to approach or exceed the upper limit of observed natural rates of extinction in the fossil record.[1] Examples of species that are particularly climate sensitive and could be at risk of significant losses include animals that are adapted to mountain environments, such as the pika; animals that are dependent on sea ice habitats, such as ringed seals and polar bears; and coldwater fish, such as salmon in the Pacific Northwest.[4][5]

References

[1] IPCC (2014). Settele, J., R. Scholes, R. Betts, S. Bunn, P. Leadley, D. Nepstad, J.T. Overpeck, and M.A. Taboada. Terrestrial and Inland Water Systems. In: Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Field, C.B., V.R. Barros, D.J. Dokken, K.J. Mach, M.D. Mastrandrea, T.E. Bilir, M. Chatterjee, K.L. Ebi, Y.O. Estrada, R.C. Genova, B. Girma, E.S. Kissel, A.N. Levy, S. MacCracken, P.R. Mastrandrea, and L.L. White (eds.) Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA.

[2] CCSP (2008). The Effects of Climate Change on Agriculture, Land Resources, Water Resources, and Biodiversity in the United States . A Report by the U.S. Climate Change Science Program and the Subcommittee on Global Change Research. Backlund, P., A. Janetos, D. Schimel, J. Hatfield, K. Boote, P. Fay, L. Hahn, C. Izaurralde, B.A. Kimball, T. Mader, J. Morgan, D. Ort, W. Polley, A. Thomson, D. Wolfe, M. Ryan, S. Archer, R. Birdsey, C. Dahm, L. Heath, J. Hicke, D. Hollinger, T. Huxman, G. Okin, R. Oren, J. Randerson, W. Schlesinger, D. Lettenmaier, D. Major, L. Poff, S. Running, L. Hansen, D. Inouye, B.P. Kelly, L Meyerson, B. Peterson, and R. Shaw. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC, USA.

[3] USGCRP (2014). Horton, R., G. Yohe, W. Easterling, R. Kates, M. Ruth, E. Sussman, A. Whelchel, D. Wolfe, and F. Lipschultz, 2014: Ch. 16: Northeast. Climate Change Impacts in the United States: The Third National Climate Assessment, J. M. Melillo, Terese (T.C.) Richmond, and G. W. Yohe, Eds., U.S. Global Change Research Program, 16-1-nn.

[4] USGCRP (2014). Groffman, P. M., P. Kareiva, S. Carter, N. B. Grimm, J. Lawler, M. Mack, V. Matzek, and H. Tallis, 2014: Ch. 8: Ecosystems, Biodiversity, and Ecosystem Services. Climate Change Impacts in the United States: The Third National Climate Assessment, J. M. Melillo, Terese (T.C.) Richmond, and G. W. Yohe, Eds., U.S. Global Change Research Program, 200-201.

[5] USGCRP (2009). Global Climate Change Impacts in the United States. “Climate Change Impacts by Sectors: Ecosystems.” Karl, T.R., J.M. Melillo, and T.C. Peterson (eds.). United States Global Change Research Program. Cambridge University Press, New York, NY, USA.

[6] USGCRP (2014). Chapin, F. S., III, S. F. Trainor, P. Cochran, H. Huntington, C. Markon, M. McCammon, A. D. McGuire, and M. Serreze, 2014: Ch. 22: Alaska. Climate Change Impacts in the United States: The Third National Climate Assessment, J. M. Melillo, Terese (T.C.) Richmond, and G. W. Yohe, Eds., U.S. Global Change Research Program, 514-536.

[7] ACIA (2004). Impacts of a Warming Arctic: Arctic Climate Impact Assessment. Arctic Climate Impact Assessment. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

[8] CCSP (2009). Thresholds of Climate Change in Ecosystems. A report by the U.S. Climate Change Science Program and the Subcommittee on Global Change Research. Fagre, D.B., Charles, C.W., Allen, C.D., Birkeland, C., Chapin, F.S. III, Groffman, P.M., Guntenspergen, G.R., Knapp, A.K., McGuire, A.D., Mulholland, P.J., Peters, D.P.C., Roby, D.D., and Sugihara, G. U.S. Geological Survey, Department of the Interior, Washington DC, USA.

[9] USGCRP (2014). Leong, J.-A., J. J. Marra, M. L. Finucane, T. Giambelluca, M. Merrifield, S. E. Miller, J. Polovina, E. Shea, M. Burkett, J. Campbell, P. Lefale, F. Lipschultz, L. Loope, D. Spooner, and B. Wang, 2014: Ch. 23: Hawai‘i and U.S. Affiliated Pacific Islands. Climate Change Impacts in the United States: The Third National Climate Assessment, J. M. Melillo, Terese (T.C.) Richmond, and G. W. Yohe, Eds., U.S. Global Change Research Program, 537-556.

[10] NRC (2008). Ecological Impacts of Climate Change. National Research Council. The National Academy Press, Washington, DC, USA.

[11] Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005). Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Biodiversity Synthesis. World Resources Institute, Washington, DC, USA.

[12] USFWS (2010). Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; 12-month Finding on a Petition to List the American Pika as Threatened or Endangered. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

[13] NRC (2008). Understanding and Responding to Climate Change: Highlights of National Academies Reports. National Research Council. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC, USA.